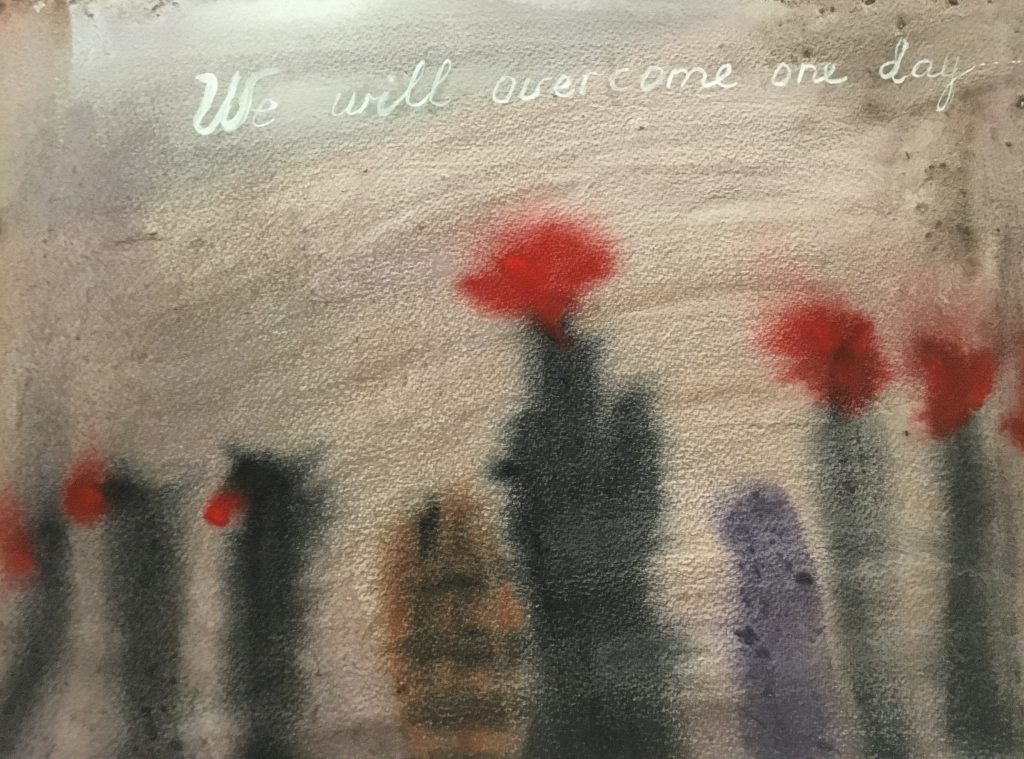

Language of Fragility/2017,Bijlmer Bajes ,Amsterdam

Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya

Language of Fragility/2017,Bijlmer Bajes ,Amsterdam

Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings, Amsterdam 2018

Artists and Refugees Unite!

We call out to you courageous creatures without jobs, visas and or status, Mothers and children, Lions, Eagles and Partridges, Winged deer, Fish, and Algae and Sea Wheat and all microorganisms, witnesses of migrants drowned on their way to Europe and to the destroyed houses and the suffering people from wars, in a word, all lives, that completed their sorrowful circle now embodied as nomadic artists. You are the new people, born from globalism, who have speed up the circulation of their cells to an impossible degree. The collective world soul is in all of us. In us dwells the soul of the great free spirits, and also the smallest leech. The strands of cosmic consciousness are interwoven in us and we remember everything, everything, everything and we relive every life over again within ourselves.

– Whose side are you on? The masters of culture, was asked long ago by Maxim Gorky.

– Artists are on the side of the weak, said Gluklya and Tsaplya.

– Where is equality, I asked the birds and they flew far away.

– Where is equality, I asked the feminists. – There is equality, but not sameness, they said.

– Where is equality, I asked the art teacher with degrees from three different European institutions

– There is no equality, he said, and that in itself is equality.

But there is equality between Refugee and Artist! We have found it!

Imagine Schiphol Airport becoming a Theatre of the Utopian Union of Unemployed People!

All new arrivals in the European Union and residents together will be actors of their own play, the play which is training mussels on the sense of true equality and justice. The European Citizenship will be judged according to the Demands of the New Theatre:

•Empathy

•Compassion and Solidarity

•Overcoming fears

•Forgiving

•Subversive Humour

•Devotion to Friends

•Sense of Entire Beauty

•Creation

Capability to reinvent yourself and move further!

These are the new demands for issuing a visa to the e world civic theatre: the start of a new society.

The new revolution will come!

We need it in order to stop the frightful course of impossible alienation and stop the destruction of the planet by means of the new attainments of equality.

There is no other way for us!

And here we are out in the street.

We do not agree that the streets where we used to shape our society should be given away. The street should be of the people. Let’s subvert the ossified order of things. Down with idiotic expensive shops! Down with the elite order of shiny trinkets that bring happiness to nobody! Down with gentrification and the brazen despotism of developers!

Architects! Do not submit! Turn down such projects! Artists! Writers! Musicians! Ecologists! Philosophers! For the sake of Refugees and all creatures: join the Utopian Unemployment Union!

Join the Potato eaters party for resistance, the Monster party for overcoming of fears, the Language of Fragility party to express your feelings, the Recycling Prison party to overhaul the system and, the Spirit of History party to bring new life to the Revolution!

Manifesto of the Utopian Union of Unemployed People written by Gluklya /Natalia Pershina -Jakimanskaya and edited by Theo Tegelaers for the performative demonstration Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings in Amsterdam 28 October 2017

Performative Laboratory )

The Utopian Union of the Unemployed is a project that brings together poets, refugees, academiks,migrants, artists and institutions in the united aim of developing a pilot model for a new type of a perforative laboratory that exists at the junction of art, economics, progressive pedagogy and the social sciences. The goals and objectives of the project are to research new methods to integrate newly-arrived refugees united them with local creative thinkers into the European Community.

UUU constituted as composition of meetings, collective walking, talks, reading groups, performative encounters. UUU can be resulted as art project or as a new relationships which can lead to long lasting collaboration based on friendship and trust .

These project starts on 2010 in St-Petersburg from the process of making video of the coinciding behaviour of the Ballerinas and Migrants from the Uzbekistan who are coming to Russia to work at the low payed and most unpleasant jobs. The idea to work with binary oppositions came from the study of the dialectical approach of the state of things .

Here is the piece of the text from these project: Our basic concept is to explore cultural encounter through the interaction between two different groups, one elite and another precarious and marginalised. For example, in Russia we are planning to bring together ballerinas and construction workers. Russian classical ballet by many is perceived as the quintessence of Russian cultural tradition, and a major cultural ‘export’. As an art form, it is characterised by the desire for order, beauty and harmony. As a cultural phenomenon, however, ballet incorporates the idea of empire, power and discipline. As an institution, it continue to be dominated by ethnic Russians. Construction work, to the opposite, is perceived as polluted, disorderly, and undesirable activity. Like in many other countries, construction workers come from undocumented migrant background, and are received with disrespect and exclusion.

In the case of Russia, we would like to make these groups to collaborate: ballerinas will come to construction sites and to observe and participate in the work done there. They will be trained and supervised by construction workers. The migrant workers from construction sites will visit Vaganov School where they, in turn, will learn the language of ballet. Each set of participants will produce an item – a dance which might lead to the installation – expressive of the difference in professions and life styles of the groups. The process will be filmed and participants interviewed after each session.

Carnival of Opressed Feelings

Michail Bachtin [From Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics]

Carnival is a pageant without footlights and without a division into performers and spectators. In carnival everyone is an active participant, everyone communes in the carnival act… The laws, prohibitions, and restrictions that determine the structure and order of ordinary, that is noncarnival, life are suspended during carnival: what is suspended first is hierarchical structure and all the forms of terror, reverence, piety, and etiquette connected with it… or any other form of inequality among people

Carnival of Opressed Feelings happened in Amsterdam in October 2017 .The hybrid of the performance and political demonstration -it is the event summarizing the seria of the workshops and encounters with refuges living at formal prison Baijlmer Bajes. It connected different people together : students ,artists ,activists, academics, people of different ages ,believes and statuses.

COF started from Bijlmer Bajes and finished at Dam square with several stops on the way.The stops where selected conceptually ,with the idea to tell refugees some alternative story about society or make a small performance. The storys was told by : Sari Akminas( (Journalist from Alepo),Khalid Jone (Activist,We are here),Ehsan Fardjadniya (artist ),Dilyara Valeeva, (Sociologist ,Uva) Erick Hagoort(curator, writer) and others and in the end Gluklya with Theo Tagelaers read the UUU Manifesto.

The structure of the performative body of Carnival is referring to the political demonstration and consists of different parties.

1) Potato Eaters party

2) Monsters party

3) Language of Fragility party

4) Recycling prison party

5) Spirits of history party

Carnival last 4 hours and brought together around 150 people.

Fragility and Resistance

Gluklya: This blouse, I call it Proletarian Madonna. You see the portrait of Anna Magnani printed on it, the actress of Pasolini’s film Mama Roma. The blouse is a character: a woman who wants to be strong, like Anna Magnani, but in fact she is not strong, she is fragile. This blouse shows the potentiality of strength without loosing fragility.

Sari: This is Gluklya’s approach to resistance. Maybe her friends share the same ideas about resistance but she uses a different method. Each person resists in his or her own way.

Erik: How can fragility be strong? How can fragility do something?

Sari: I regularly visited Gluklya’s studio here at Lola Lik, where I work. Each week I saw more and more drawings and more costumes. They evolved from the Language of Fragility game, in which words, sounds and images are combined in an associative way. In this game newcomers combine Dutch words with words that sound the same in their own language but mean something completely different. For instance the word ‘gras’ in Dutch is pronounced the same as the word ‘gras’ in Arabic. In Dutch it means the green grass, but in Arabic it means punishment, in Dutch ‘straf’. One of the newcomers, Marwa Aboud, made many beautiful drawings of these kind of different meanings of the same words. Later on also costumes were made that referred to the images of this game. At first it was a fragile process. Fragile images. Now it is still fragile but this fragility is somehow growing, it is building up and building up and in the end can become something powerful. Imagine there is only one tiny hole high up there in this studio to get out. What we do here is building and building until we reach that hole. But still we cannot pass it, so we need more pressure. The fragility is pushing and pushing until we can go through this hole and get out.

Gluklya: Like through the eye of a needle.

Sari: With fragility you can build up pressure. Not like an explosion making a lot of mess but like an escape from prison, finding a way to escape, although it seems impossible.

Gluklya: We maybe have to find a word next to fragility. Fragility and? There has to be this other word.

Erik: What do you mean?

Gluklya: I mean, through what can we think about fragility as resistance? What kind of method or strategy can help to think about fragility as something strong?

Sari: Change?

Gluklya: I don’t think that art can effect change literally. There is a tendency among artists to strive with their art for real change in society. Artists are allowed to do whatever, to be crazy and to play, in a confined area, in the sand. Suddenly they wake up and they realize that art has become a Kindergarten. It is good to realize this, but I think you shouldn’t hysterically rush and presume that you can change society with your art.

Sari: In my experience in this war, in Syria, there have been artists who could disconnect themselves from the actual war. There were artists from the academy of fine arts in Damascus who were making drawings of sunflowers on the walls of houses. As a journalist I was startled at first. There is a war going on! But then I realized that it can be important to paint flowers when everything around you is about killing and destruction. Then it is wonderful to make or to see something that is different. To see something relaxed. A break, a small break because you will be back in the reality of the war anyhow. Next to this, when artists are only busy with political action and making work about the war, the war can become something to exploit, something commerical even. As an artist you shouldn’t do what people expect you to do, you can have your own way of dealing with the situation without being involved directly in the actual fire of the war. That can be a form of resistance too. To guard or reserve this other reality than the reality of the war. Everybody is an artist and everybody has a unique way.

Erik: Joseph Beuys.

Gluklya: Well, there is a social worker here at Lola Lik who said this. She makes statements like those of Joseph Beuys and she organizes daily creativity activities to involve refugees. The intentions are good. She means that everybody is an artist because everybody is displaced. You can be displaced by forced migration. That is clear. In her opinion artists are also displaced, metaphorically speaking, because they are displaced in their minds. It’s her idea. I’m not sure about it.

There is this policy here at the AZC that you may not push. You only can do what refugees want to do themselves. That means in my opinion that you become like a social worker. You reduce yourself to a neutral person, who is just observing, facilitating and giving advices a little bit. For social work that can be very good. But for art I think some other strategy is needed.

Sari: I have come into this other country, I have to obey other rules and to follow other customs. After two years I finally think I know how things work here. I am slowly gaining control of my own life again. This takes time. It really takes time. I knew this when I came here. I realized from the start that this all would take time. But the experience is something else. Not everybody can handle it. Some people close themselves off, others get frustrated, angry. But when you are in a new situation you need time to adapt. Adaptation. Some people adapt fast. Some people adapt slowly. Adaptation, that would be my word. It is not passive adjustment. Adaptation helps you to gain control and to become strong without loosing your own way, your own personality.

Gluklya: You cannot force people to be interested. I’ve learned to leave it up to the people here to find out what they want. But what if they don’t know what they want? Then, in my experience, somehow, you need to jump, together, it is a feeling, it’s very hard to put it in words, you approach each other as humans, you take each other serious, you treat each other as equals. You shouldn’t be too careful, you shouldn’t be afraid to approach the other. Better to make mistakes than to stay in a situation of vague intentions.

Erik: Disguise. That could also be a word to think about a method. Disguise is not just that you appear in a different way, for instance by dressing up. There is something of a purpose. You can take on an appearance in order to get access to a different environment. In disguise you can mingle among familiar people without being recognized or you can mingle among unfamiliar people without being noticed as somebody from outside. You can do this for fun but also with a particular purpose, for example to get access to the truth, as in research journalism. Disguise somehow blurs the line between being honest and cheating.

Gluklya: Vermomming. In Russian it is maskirovka. Hiding. Behind a mask.

Erik: Hiding but in an active way. In disguise you can be present, visible, active.

Sari: From another perspective, disguise can be forced. You can be in a certain situation that you can only handle or survive by hiding your true personality. That is also some form of disguise. When you don’t feel comfortable with a situation, you can opt for fitting in, in disguise. Or if possible you also can opt for leaving, walking out of the situation. Disguise in Arabic is: el tachefie. The source of the word is ‘ichfa’. ‘Ichfa’ means vanish. So you vanish behind your mask. But you also can vanish by walking out of the situation. You become a refugee. The idea of language of fragility plays with the idea of different ways of hiding, different meanings behind the masks of the words.

Erik: Because of a mask or because of a costume, some people can be more honest. Or it is a way to be honest. In disguise you might do something or you might say something that you otherwise maybe would not dare to do or say. Maybe the same counts for the Carnival of Oppressed Feelings?

Sari: People will see the costume but they cannot point to a specific person. So the costume does this or that, the character says this or that. That can help to express your feelings.

Erik: Then who is accountable? If you say things or do things and people want to address you, you cannot just say: I didn’t say this, it was carnival.

Sari: Sure, when you go in disguise, you should think of or at least try to think of the consequences of what you do. You have to think about what will happen when you take off your mask and reveal who you are. If you are not ready to face the consequences, whatever they are, then you shouldn’t go in disguise.

Erik: Your drawings and costumes are worlds in themselves. They depict a ‘language of fragility’. There is beauty there and also monstrosity, anxiety, frailty, power. It is already there, in the drawings and in the costumes. From an aesthetic point of view they actually don’t need anything extra to be appreciated. But you bring them into a charged public sphere, as part of a carnival that is also a demonstration with explicit political demands. In my experience some of the images and some of the costumes playfully resist to be used politically: walking chairs; running plants; eerie screaming creatures; banners that read ‘forgiveness’ or ‘doubt’. They resist appropriation.

Gluklya: To me this is a dilemma. I try to combine. That would be the word for me to be able to work with fragility. To combine is maybe my method or my strategy. Many people say to me: that is not possible, it is this or that. You must choose, they say. Lately I was reading Gayatra Spivak’s book “Why …. cannot speak”. According to her we shouldn’t think like black-white, either-or. That kind of thinking confirms distinctions and forces to choose between positions. Better not to choose. This sounds quite opportunistic from a political point of view, but from an artistic point of view I think it is important. Try to connect, to combine, to do both, to balance. So I continue to follow this path, to be somehow inside and outside… fragility and power… art and politics. Like jumping in and out of the water, moving like a dolphin.

This is an edited compilation by Erik Hagoort of several conversations between Sari Akminas, Gluklya and Erik Hagoort in Gluklya’s studio at Lola Lik, 2017.