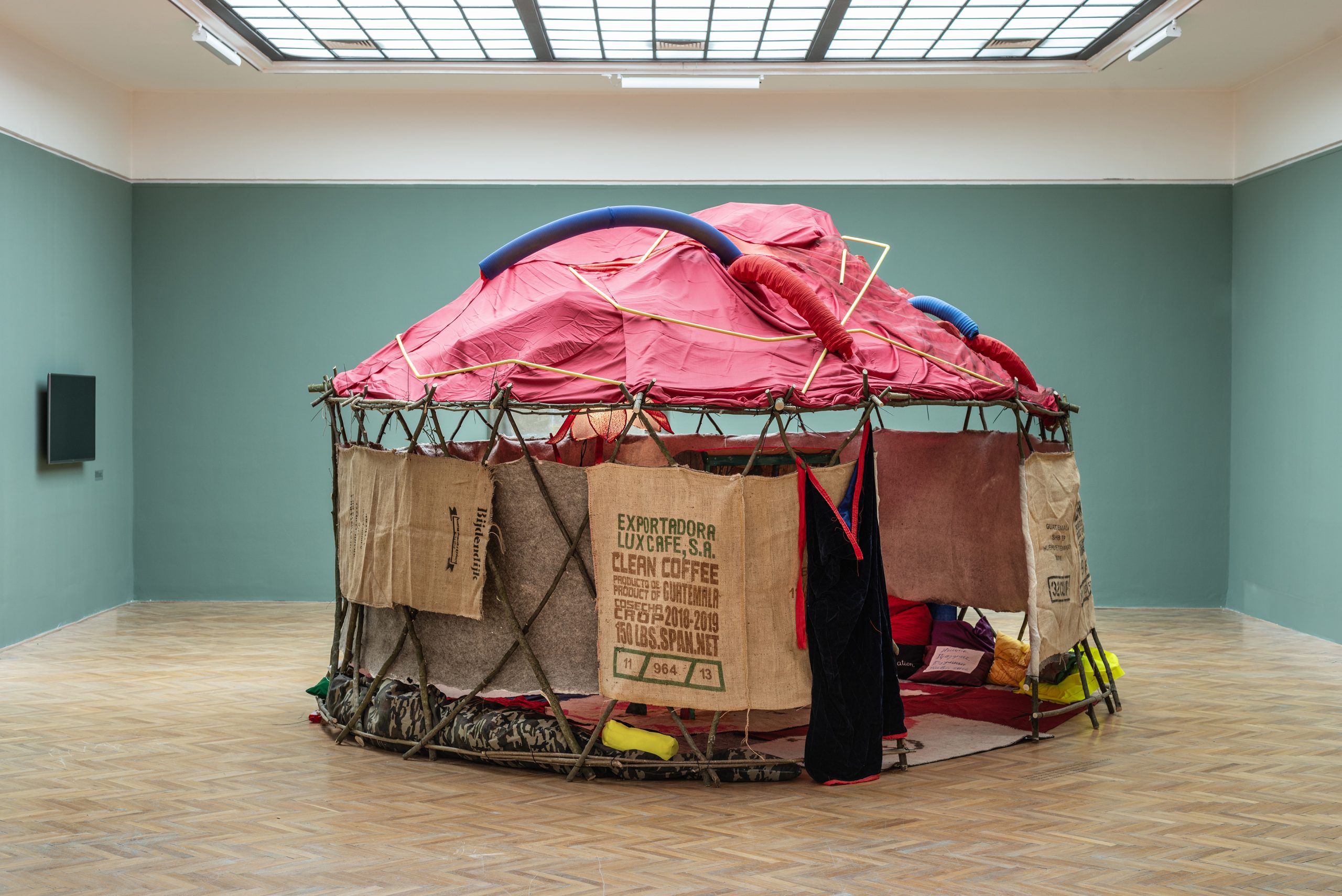

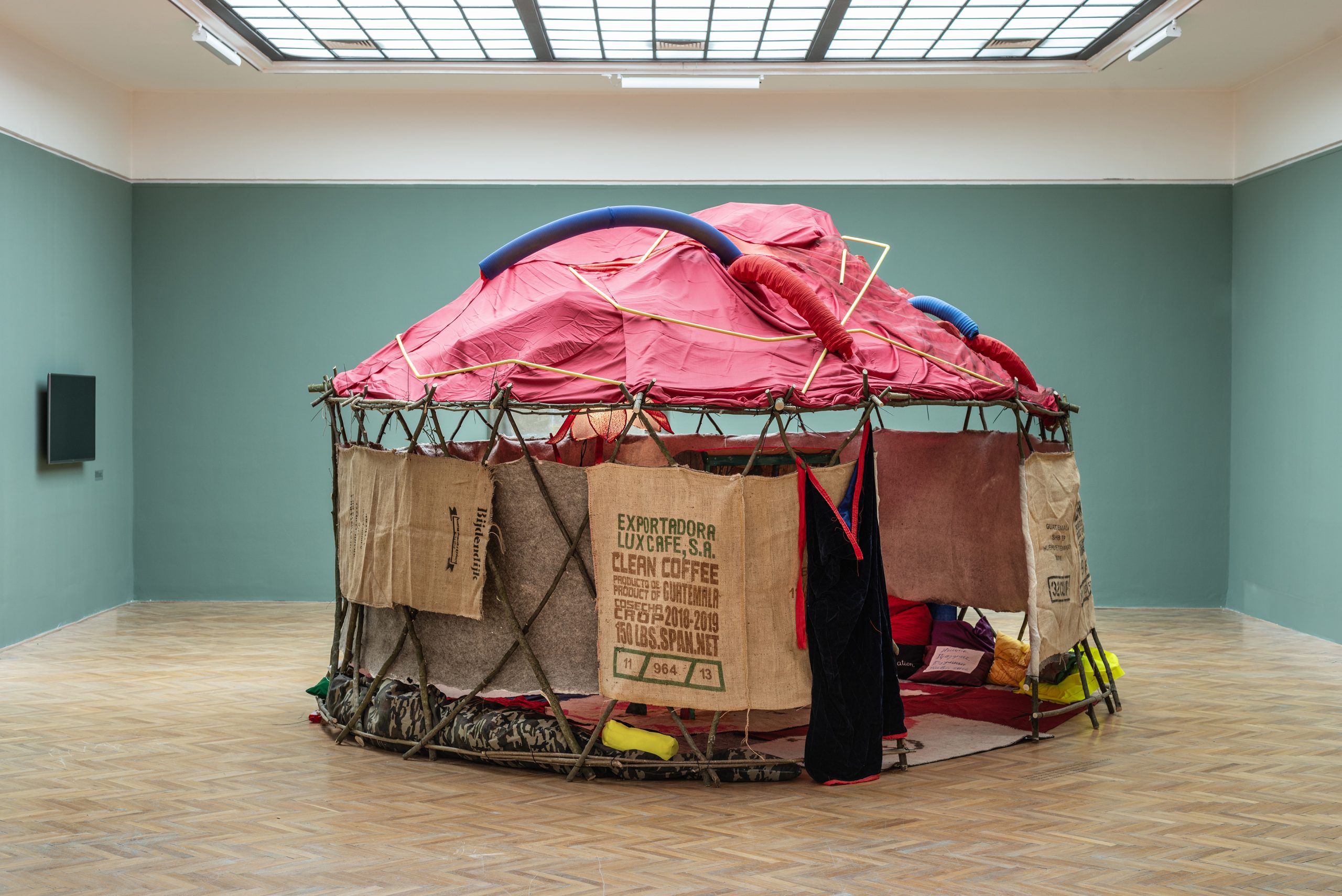

4 m in diameter x 1.65 m height

Wooden sticks, textiles, plastic tubes, conceptual pillows, the body of Shahmaran (soft sculpture), chair for two people with the book: Two Dairies: Gluklya and Murad

Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya

4 m in diameter x 1.65 m height

Wooden sticks, textiles, plastic tubes, conceptual pillows, the body of Shahmaran (soft sculpture), chair for two people with the book: Two Dairies: Gluklya and Murad

Exhibition “Images of Power”, Textile Biennale, Museum Rijswijk, Netherlands. Curated by Diana Wind.

The war in Ukraine has again brought a centuries-old crime against women and also men to our attention. In the past century, stories about rape, abuse and terror only made the news afterwards, sometimes even years later, because the suffering that a war brings had to be dealt with in its entirety, perpetrators and victims had to find their place again. An example is the 70,000 ‘comfort women’ who were forced to work as sex slaves in army and navy brothels during the Japanese occupation of the former Dutch East Indies between 1942 and 1945.

To those who have no time to play is structured around four stories drawn from the artist’s own experiences. Each narrative is represented by its own form of architecture and mode of reception. As someone looking at the exhibition, you are asked to perform different roles during your time there. You become a reader, a viewer, a listener, an emotional participant, an outsider caught in the midst of a protest, a collective presence in a chorus of sewing machines or any number of other roles you can define for yourself. There is a beauty in how the exhibition unfolds and how your attention is called to other people’s struggles that ask to become part of your own, if only for a little while.

from the curatorial text by Charles Esche “Who has no time to play?” (page 35)

Continue reading “To Those Who Have No Time to Play 2022-23”

Exhibition “The New Subject. Mutating Rights and Emerging Challenges of Living Bodies”, Kunsthal NORD, Aalborg, Denmark 2023. Curated by TOK (Anna Bitkina and Maria Veits) and Cathrine Gamst. Photo: Simon Bendix.

EMPOWERING VULNERABILITY,2024

Textile objects and a series of drawings

The installation presents Gluklya’s body of work, spanning from the post-Soviet context in 2006 to the present day in 2023, all bound together by the theme of politicized vulnerability. It comprises watercolors and conceptual clothing, both of which delve into the darker aspects of femininity. This thought-provoking exhibit invites viewers to contemplate the societal expectations and stereotypical roles imposed upon us.

Visual correspondence between Gluklya and Kati Horna

GALLLERIAPIÙ

opening 26/02/2022

27/02 > 30/04/2022

« On the ground floor there was a rectangular garden, full of flowering plants and tall trees whose branches reached up to the second floor. Kati was in charge of watering it, and in the meantime she photographed every flower, every leaf, every insect. Suddenly we heard her screaming, she was calling us. We thought she got hurt. Leonora, Chiki, Gaby, Pablo, José, the dog and I,we all rushed down the stairs together, we were frightened. Kati, perfectly fine, was photographing a chrysalis. “Look, this is the divine moment! The caterpillar is dying and the butterfly has yet to be born. What for one is a coffin for the other is a crib. But if the caterpillar has ceased to exist, the butterfly does not exist yet. In short, no one exists at the moment. I’m photographing nothing .. ”

AAC Galerie Weimar

Denunziation

12.12.2021 – 02.04,2022

“They are among us” is an installation conceived especially for the ACC using objects of clothing, light, and sound of the metronome, which was inspired by current and historical cases of denunciation, including those surrounding the ‘witch hunts’ and the Gulag under Stalin. The work seeks to reproduce in the exhibition space a sphere of uncertainty and anxiety in which the denounced do not know who the denunciator is and whether he is not even directly present himself.

The atmosphere of the installation reproduces the atmosphere of suspicion when at vernissage people for sure knows that denunciator came, but they did not know who is he or she. It can be any person. It is the everyday reality in Russia, Belorussia, Ukraine, and many other countries.

group show NEST / Den Haag ,10 September 2021

Propaganda Flowers is a series of drawings that are accompanied by stories from interviews with people from different countries on the connection between politics and flowers. For example, the Kimilsungia violet orchid was named after Kim Il-Sung, former leader of North Korea, and tells a narrative about the remembrances of socialism. The Vampire Tulip asks questions about human hypocrisy, distracted from the water crisis in Africa, whereas the Welwitschia flower is accompanied by the text about the flower as a symbol for democracy. Each drawing touches upon the ethics of politics, combining the sweet symbolism of flowers with deep geopolitical concerns.

For the exhibition at Nest in The Hague, Can you be a revolutionary and still like flowers?, a new chapter of the Propaganda Flowers series was created. The works was done in the context of Russia , with supportive conversations with the eco -activist Maria Tinika who created a Saving Trees society in St -Petersburg.

photo documentation of the Installation : Charlott Markus

Reviews:

Den Haag Centraal: https://www.nestruimte.nl/bloemen-als-symbolen-van-verzet/

Groene Amsterdammer: https://www.groene.nl/artikel/de-laatste-sanseveria and https://www.groene.nl/artikel/dansende-bloemen

Van Abbe Museum ,POSITIONS # 4

Positions #4 introduces the work of four international artists – two individuals and one group: Gluklya(Natalia Pershina -Jakimanskaya), Sandi Hilal & Alessandro Petti and Naeem Mohaiemen. These artists all share an activist practice that draws on the history of colonialism, occupation and political conflict to make work about living in the world today.

The exhibition includes film, drawing, architecture, models, archives, texts and clothing to build up elaborate images of particular parts of the world and conditions in places both near and far away from Eindhoven. Often the artistic practices sit at the crossroads of cultural anthropology, forensic science, documentary filmmaking, self-organization and collaboration. All four artists teach us – each in a different way – about the capacity of different minorities and marginal communities to cope with difficult life situations and survive, if not thrive, despite the powers exercised over them.

Carnival is trying to Overcome Suffering

Gluklya’s practice simulates current socio-political urgencies and it contests power structures that function in the public urban space. Gluklya’s work process is distinguished by playfulness, as her studio turns into a meeting point where diverse collaborators work together on translating mutual socio-political inquiries into conceptualized clothes and other useable artistic items, which are later applied within further performance activities characterised by protest gestures in the public space.

In 2017, Gluklya’s studio was located in the former prison Bijlmerbajes, where different artists, refugees, and other cultural NGO’s activities were accommodated. Motivated by the unique location of her studio and its surrounding, she initiated the Utopian Unemployment Union(UUU), a platform where various collaborations have been created, including long-term relations with refugees, asylum seekers, students, different art-practitioners, scholars and other people. Under the umbrella of the ‘UUU’ and in collaboration with TAAK and her collaborators, Gluklya developed the ‘Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings’ – a protest performance in the public space of the city, that took place in the route between Bijlmerbajes and Dam square in Amsterdam.

Afterall Journal 2019

http://gluklya.com/publications/building-social-interdependency-gluklyas-feminist-practice/

Installation, mix textile, wood, hand writing

43 sticks x 3 m high

56 Venice Biennale, «All the Worlds Futures » 2015

The work originated with Protest Clothes which participated in real street protests in St. Petersburg in 2011-2012. However, only a few of those survived; the rest were new. The objects are thus “re-created” representatives of protesters with different political positions. Most of the objects included written slogans. The slogans have been divided into two categories: “Real” slogans people were screaming during the protests (“A Thief Must Sit in Jail”, “Bring Back Our voices”, “Russia Will be Free”, “The anti-abortion law is Russia’s shame”, “Vova, cut the crap and piss off”, “Russia without Putin”) and the “Utopian” ones, invented by me or my friends, that represent imaginative longing for a better society (“Artists and Migrants Unite”, “Does Russian Mean Orthodox?”, “Students and Veterans against Criminals”)

Interview with Anna Battista

http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/society/2015/05/150509_venice_biennale_review_kan

Do you remember how you chose what to wear to the protests of 2011-2013? In winter, people got their white summer trousers out of the closet and bought white scarves and flowers. I remember how on Strastnoy Boulevard a “white knight” appeared, walking toward me out of a restaurant, carrying a bouquet of white chrysanthemums, a crane’s pink beak on his nose. Slightly drunk, smiling blissfully, he folded a couple of paper beaks for us, and we attached ourselves to the zany flock of the insubordinate.

What nostalgia we feel today, looking back at those white jackets, trousers and scarves that were our protest clothes! They hang gloomily on our hangers, tired and disappointed, or lie on shelves, remembering their glory days at the carnival, when they found their voice and served not merely to clothe the body, but, unthinkable as it may seem, to expose the emperor’s lack of new clothes.

An artist from Saint Petersburg with the childish-sounding pseudonym of “Gluklya” (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya) treats a piece of clothing as a living being. Anna Tolstova notes that “the most ordinary dress—fragile, throwaway, worthless, the ridiculous and frivolous material that the FFC [Factory of Found Clothes] works with in performances, video and installations, was conceptualized as a kind of pan-human universal, emerging from the everyday and inserting itself into culture. The dress is both a protector of the body’s memory with its intimate experiences, a record of cultural and subcultural codes, a political manifesto, and a weapon of resistance against gender and social stereotypes.” (http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2394738)

Clothes have a life of their own: they travel, march with students, go into seclusion, go scuba diving, they may even, following in the footsteps of “Poor Liza,” jump into the Small Swan Canal (http://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/history/10/982/), or they may go to a protest march against the falsification of elections. Gluklya’s installation at the Venice Biennial is called “Clothing for Demonstrations Against Vladimir Putin’s False Elections in 2011–2015.”

Gluklya has a special affection for white clothes, and does not like new clothes, which have no personal stories to tell. In her creative duet with Tsaplya (Olga Egorova) the two of them created the FFC (Factory of Found Clothes), which existed until 2014. I have always loved Andrei Bely and his metaphysics of the color white, so I therefore immediately took to calling the artist Belaya (White) Gluklya, all the more appropriate since one of the installations of the Gluklya-Tsaplya duet was entitled “The Psychotherapy Cabinet of the Whites” (2003).

Love for old white clothing fits perfectly with the theme of the white ribbon movement, which very quickly dropped into the past and simultaneously lives on in the protests and repressive actions of the present.

The hopes connected with these clothes have been replaced by apathy and despair; the Bolotnaya Square case became a new triumph of lawlessness and fortified the feeling of hopelessness. The subject of protests is in many ways a traumatic one: those who went out on the streets then were victims of injustice and violence, who soon became victims of a new violence, spreading into the bloodletting on the soil of Ukraine.

The white ribbon protests abound with stories, faces, images and themes that present a rich narrative for art, including the art of representing political practices, which Pyotr Pavlensky calls art about politics, as opposed to political activism using art as a means of direct action.

In an interview with Radio Svoboda, http://www.svoboda.org/content/article/27049832.html Gluklya said that the installation contains “a certain amount of ambivalence, without which, in my view, art does not exist. But at the same time it was very important for me to leave it ‘black and white’ in terms of my position. And that was a surprisingly difficult task. All my energy went into that.” Her mighty effort created a multiplicity of meanings.

Ghosts on Stilts

A few dozen tall T-shaped wooden poles stand by the wall. “Talking” clothes with slogans delicately embroidered in red on a white background (such as “Russia will be free”) hang upon them, with others written in black on white or orange (“You can’t even imagine us,” “NO,” “Power to the millions, not the millionaires,” “America gave me $10 to stand here,” “Does Russian mean Orthodox?” on a Russian Railways vest), or in red on black (“A thief must sit in jail”).

They look like a column of ghosts who have stepped out of the void to remind us about the recent demonstrations. These apparitions appear to be the rebellious spirits of protest. One-legged, they also bring to mind clowns on stilts, conveying the carnivalistic atmosphere of the first marches and rallies. The associations with ghosts and clowns add a multitude of visual and literary resonances to the viewer’s impression.

Tau Crosses

A simple pole with a crossbeam was used in the southern and eastern parts of the Roman Empire as a site of execution, on which criminals were crucified. This type of cross is known by various names: Tau cross (after the letter in the Greek alphabet), St. Anthony’s cross, crux сommissa, among others. It is highly probable that Yeshua of Nazareth was crucified on just such a cross. There is also a long white shirt—the charred “sackcloth of shame” in which criminals were led around the city—reminiscent of the robes of Christ.

The wall of “elevation of the cross” references Christian images of crucifixion, and more broadly, the typology of execution. The artist seems to have created an amalgam of different types of lethal execution: the trousers without a top and the shirt without trousers conjure up a dismembered body, the dress on poles a beheaded, hanged, or crucified one, and what is more, they are all placed up against the wall, as if in front of a firing squad.

This array of crucifixions can be seen, of course, as hyperbole about repressions or the expectation of wholesale slaughters of protesters, but today, with the police ready to declare their right to shoot in crowded places, including at women, Gluklya’s installation looks like something out of the evening news.

The Female Body

There is a girl’s white dress bordered with a blood-red thread; a ballet tutu with a rusty hammer-and-sickle bottle opener in place of a head (a vivid symbol of our culture); on the back of an overcoat, an image of a woman being dragged into a paddy wagon by OMON agents (riot police); on a summer frock, a drawing of a “witch” tied to the stake, on fire.

The theme of the sacrifice of women puts the viewer in mind of Pussy Riot, who have elicited people’s bloodthirsty fantasies and calls for the most horrendously cruel forms of punishment (pussyriotlist.com). The exhibit also contains headgear made to resemble a balaclava helmet. Not explicit, but ambivalent, a kind of hint.

Gender violence is one of the recurring themes of the tragic parade of clothes. It seems to be no accident that Gluklya’s exhibit at the Venice Biennial opened around the same time as Alketa Xhafa-Mripa’s installation at the stadium in Prishtina, Kosovo (http://www.wonderzine.com/wonderzine/life/news/214075-thinking-of-you; Xhafa-Mripa, born in Kosovo, lives in Great Britain): there, a few thousand dresses and skirts, hung up on white ropes, testify to the sexual violence that occurred on a mass scale during the armed conflict in Kosovo of 1998–1999.

Dress Code

In Ludmila Ulitskaya’s novel The Funeral Party, Robins formerly Rabinovich, the far-sighted owner of a funeral home, “had difficulty in determining the client’s property status” at a funeral attended not only by Jews but also by blacks, American Indians, rich Anglo-Saxons and “numerous Russians,” comprising both “respectable citizens” and “out-and-out scoundrels.” Can social status be determined by protest clothing? Here, too, were various sorts of people: office clerks in waistcoats, hippie-punk-goths, sophisticated women and Poor Lizas, ballerinas and Lovelaces. Their clothing—the body of their souls—is torn and in danger. They, too, are the targets of Gluklya’s reproach: “Are all of us really like this torn old rag?”

A l’Arsenal, c’est l’artiste russe Gluklya qui dénonce le durcissement du régime de Moscou, à travers ses “Vêtements pour manifestations contre de fausses élections de Vladimir Poutine”.

Perchés sur des madriers en bois, ces drôles de pièces de tissu portent des messages en russe: “un voleur doit être assis en prison”, “je veux que la Russie devienne le plus beau pays du monde” ou seulement “va-t-en”.