Carnival and Dialogue

Erik Hagoort, 2018

“Carnival is a pageant without a stage and without a division into performers and spectators. (…). The carnivalistic life is life drawn out if its usual rut, it is to a degree “life turned inside out.”

(Bakhtin 1973, p. 101)

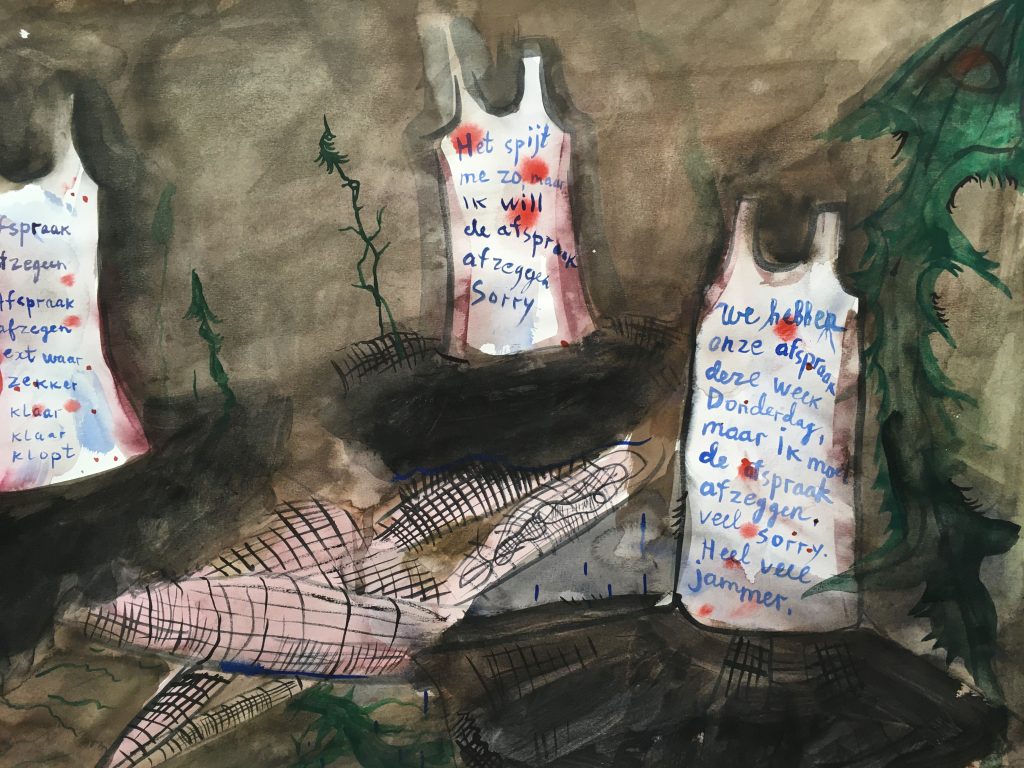

These lucid thoughts about carnival by the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975) artist Gluklya founded to “defend ”her desire to realize the performance of the Carnival of Oppressed Feelings, which took place on October 28, 2017 in Amsterdam, supported by curating collective TAAK and , Mondrian and AFK Fund .

Bakthin’s interest in carnival is widely known. He especially paid attention to the medieval festival of fools. During this festival the world appeared to be upside down. The king could dress up as a joker, the priest as a buffoon, the servant as a nobleman, the thief as a judge, and they would all mock each other. The festival of fools was not organized as a parade of performers marching while spectators were looking on from the side. The whole of society participated, more or less. It was a parody of reality, a temporary reversal of social hierarchies and roles. For a couple of days. After that the usual relations were restored. Some even say that the festival of fools could only happen or was allowed to happen, because everybody already knew that it would not have a lasting effect: just a play, society holding a mirror to itself, but without consequences.

In Bakhtin’s opinion carnival is not a playful exception; it has continuity, it sustains for real. The feast installs a consciousness of the possibility that society could be upside down, that existing structures are more or less relative or that established roles can be mocked. This awareness is put into practice. After carnival, the costumes are cared for, they are stored and repaired. People soon start to work on making other costumes for next year. New songs are composed, new tricks and jokes. These practices serve to maintain and renew carnival. Carnival is present throughout the whole year.

Bakhtins ideas about carnival makes me think of a connection between carnival and dialogue. Next to carnival dialogue is one of the main topics of Bakhtin’s writings. He invites us to jump from thinking about carnival to thinking about dialogue, and back again. At first sight, this seems rather puzzling. A dialogue does not have much in common with carnival. To have a dialogue, to have a good talk on a matter of importance, to have a meaningful conversation, to learn to understand each other: that seems to be far off an event in which the world appears to be upside down.

In a dialogue you respond to somebody else. In a dialogue you try to articulate in words what you want to express. You are urged to choose your words carefully and to say what you want to say in a way that the other one can get it. In a dialogue you want to understand each other. The conversation partners need to know each other’s use of language and to speak properly, at least to be able to grasp what the other is saying. There is a clear division in roles: when you speak, the other one listens. You don’t speak both at the same time. There is also a clear distance between the conversation partners. There is clarity about who is who: you speak with another person while you see this person face to face and while you concentrate on what the other one says.

Attention, concentration, articulation: this is all very different from carnival. In carnival you don’t need to have a good talk. Carnival is not about understanding each other, it is not about being articulate about what you mean. The more you are involved in the carnival, the less articulate you may become. You drink and dance, you watch and move. You don’t always know who is who. You meet others in disguise. Everybody can speak at the same time, so no one can really hear what the other is saying. In carnival there is no focus, there is no direction. Distraction rules. Roles and positions are allowed to become blurred. And, in carnival expressions are for a big part non-verbal: you communicate with gestures, touch, music, sound, color, costumes, images. The intention of carnival is: carnival.

By reading Bakhtin it becomes apparent that carnival and dialogue might have something in common. A dialogue is not a performance of a dialogue. A dialogue happens as it evolves. It is lived experience. It is a lived experience that you produce together. You yourself and the other with whom you are talking both produce the conversation in which both of you are participating. Just like in carnival. Carnival is also not a performance but a lived experience: “Carnival is not contemplated, it is, strictly speaking, not even played out; its participants live in it”, (Bakhtin 1973, p. 100). People produce the carnival by participating in it. It can only happen because the participants make it happen together.

Carnival and dialogue also share indeterminacy. Even when you have an articulate conversation, this conversation emerges and evolves. It is a provisional, temporary event on which no one of the participants is in full control.

By listening to what somebody else says,

or by responding to what somebody else says,

you both create what otherwise would not be there.

When you speak you can not fix the meaning of your own words.

When you speak you can not define what the other one will do with your words.

This does not mean that you are out of control. No one else than you yourself has the relation to your own words at the moment that you produce them.

The same counts for the other one. Each of you is responsible for one’s own contribution to the conversation. But no one of you owns this conversation, no one of you can have the talk just for him- or herself. A conversation somehow exists not only in your own experience, not only in the other person’s experience either, but outside both of you, it evolves as an extra-experience, an extra-ordinary experience, in which both of you share.

Dialogue is a joint provisional creation. Like carnival. It is provisional, because it is only there at the moment of its realization. Not before and not after. But it may have a lasting impact, not only because a dialogue can make a change in what you think, but also because you can take care of it later, when the dialogue is not there anymore. You can memorize the conversation, you can write it down, you can think it over again, you can develop your thoughts further and then continue the conversation later, when you meet up again with your conversation partner. So although the conversation has ended, it may continue to play a role in your daily life.

So, in carnival and in dialogue we produce the extra-ordinary by participating in it. We care for these extra-ordinary events

when they are not there anymore

when they are not there yet.

Dialogue can be considered a carnivalesque event

Carnival can be considered a dialogical event.

Dialogue as a carnival in words.

Carnival as a dialogue in disguise.

This is the text of a speech by Erik Hagoort by invitation of TAAK

Post-Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings

14 December 2017

Tolhuistuin, Amsterdam

With Maral Noshad Sharifi, Charles Esche, Ehsan Fardjadniya, Erik Hagoort, Gluklya and others.

Source: Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, translated by R.W. Rotsel, Ardis, USA 1973.