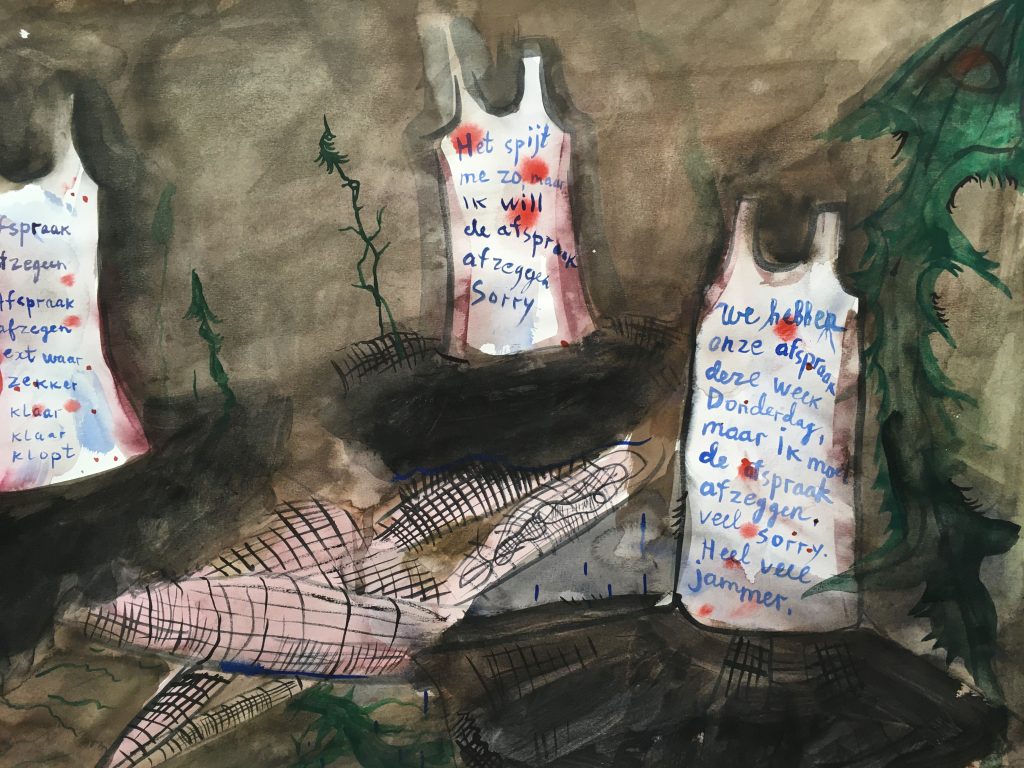

Afspraak afzeggen 2016

These drawing was made some time back ,during my time for the preparation to Dutch exam for getting the Eu passport. The sentence Afspraak afzeggen ,written in the shirts ,means :Appointment Canceled . It is about how you are feeling when your appointment, which you are waiting and carefully preparing suddenly canceled.

Material : whatecolour,64x50sm

All The World’s Futures – Venice Biennale Arte 2015

Interview with Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya – Russia), one of the artists selected to participate in the exhibition,All The World’s Futures – Biennale Arte 2015. Exhibited at the Arsenale Corderie.

Publications about Venice Biennale

Venice Biennale: The Overproduct of Art?

http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/society/2015/05/150509_venice_biennale_review_kan

Mass Protest against Putin continue… in Venice. The Work of Factory of Found Clothes at the Venice Biennale

Elena Volkova The Protest Dress: Shoot Them By Hanging (Gluklya at the Venice Biennial)

Do you remember how you chose what to wear to the protests of 2011-2013? In winter, people got their white summer trousers out of the closet and bought white scarves and flowers. I remember how on Strastnoy Boulevard a “white knight” appeared, walking toward me out of a restaurant, carrying a bouquet of white chrysanthemums, a crane’s pink beak on his nose. Slightly drunk, smiling blissfully, he folded a couple of paper beaks for us, and we attached ourselves to the zany flock of the insubordinate.

What nostalgia we feel today, looking back at those white jackets, trousers and scarves that were our protest clothes! They hang gloomily on our hangers, tired and disappointed, or lie on shelves, remembering their glory days at the carnival, when they found their voice and served not merely to clothe the body, but, unthinkable as it may seem, to expose the emperor’s lack of new clothes.

An artist from Saint Petersburg with the childish-sounding pseudonym of “Gluklya” (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya) treats a piece of clothing as a living being. Anna Tolstova notes that “the most ordinary dress—fragile, throwaway, worthless, the ridiculous and frivolous material that the FFC [Factory of Found Clothes] works with in performances, video and installations, was conceptualized as a kind of pan-human universal, emerging from the everyday and inserting itself into culture. The dress is both a protector of the body’s memory with its intimate experiences, a record of cultural and subcultural codes, a political manifesto, and a weapon of resistance against gender and social stereotypes.” (http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2394738)

Clothes have a life of their own: they travel, march with students, go into seclusion, go scuba diving, they may even, following in the footsteps of “Poor Liza,” jump into the Small Swan Canal (http://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/history/10/982/), or they may go to a protest march against the falsification of elections. Gluklya’s installation at the Venice Biennial is called “Clothing for Demonstrations Against Vladimir Putin’s False Elections in 2011–2015.”

Gluklya has a special affection for white clothes, and does not like new clothes, which have no personal stories to tell. In her creative duet with Tsaplya (Olga Egorova) the two of them created the FFC (Factory of Found Clothes), which existed until 2014. I have always loved Andrei Bely and his metaphysics of the color white, so I therefore immediately took to calling the artist Belaya (White) Gluklya, all the more appropriate since one of the installations of the Gluklya-Tsaplya duet was entitled “The Psychotherapy Cabinet of the Whites” (2003).

Love for old white clothing fits perfectly with the theme of the white ribbon movement, which very quickly dropped into the past and simultaneously lives on in the protests and repressive actions of the present.

The hopes connected with these clothes have been replaced by apathy and despair; the Bolotnaya Square case became a new triumph of lawlessness and fortified the feeling of hopelessness. The subject of protests is in many ways a traumatic one: those who went out on the streets then were victims of injustice and violence, who soon became victims of a new violence, spreading into the bloodletting on the soil of Ukraine.

The white ribbon protests abound with stories, faces, images and themes that present a rich narrative for art, including the art of representing political practices, which Pyotr Pavlensky calls art about politics, as opposed to political activism using art as a means of direct action.

In an interview with Radio Svoboda, http://www.svoboda.org/content/article/27049832.html Gluklya said that the installation contains “a certain amount of ambivalence, without which, in my view, art does not exist. But at the same time it was very important for me to leave it ‘black and white’ in terms of my position. And that was a surprisingly difficult task. All my energy went into that.” Her mighty effort created a multiplicity of meanings.

Ghosts on Stilts

A few dozen tall T-shaped wooden poles stand by the wall. “Talking” clothes with slogans delicately embroidered in red on a white background (such as “Russia will be free”) hang upon them, with others written in black on white or orange (“You can’t even imagine us,” “NO,” “Power to the millions, not the millionaires,” “America gave me $10 to stand here,” “Does Russian mean Orthodox?” on a Russian Railways vest), or in red on black (“A thief must sit in jail”).

They look like a column of ghosts who have stepped out of the void to remind us about the recent demonstrations. These apparitions appear to be the rebellious spirits of protest. One-legged, they also bring to mind clowns on stilts, conveying the carnivalistic atmosphere of the first marches and rallies. The associations with ghosts and clowns add a multitude of visual and literary resonances to the viewer’s impression.

Tau Crosses

A simple pole with a crossbeam was used in the southern and eastern parts of the Roman Empire as a site of execution, on which criminals were crucified. This type of cross is known by various names: Tau cross (after the letter in the Greek alphabet), St. Anthony’s cross, crux сommissa, among others. It is highly probable that Yeshua of Nazareth was crucified on just such a cross. There is also a long white shirt—the charred “sackcloth of shame” in which criminals were led around the city—reminiscent of the robes of Christ.

The wall of “elevation of the cross” references Christian images of crucifixion, and more broadly, the typology of execution. The artist seems to have created an amalgam of different types of lethal execution: the trousers without a top and the shirt without trousers conjure up a dismembered body, the dress on poles a beheaded, hanged, or crucified one, and what is more, they are all placed up against the wall, as if in front of a firing squad.

This array of crucifixions can be seen, of course, as hyperbole about repressions or the expectation of wholesale slaughters of protesters, but today, with the police ready to declare their right to shoot in crowded places, including at women, Gluklya’s installation looks like something out of the evening news.

The Female Body

There is a girl’s white dress bordered with a blood-red thread; a ballet tutu with a rusty hammer-and-sickle bottle opener in place of a head (a vivid symbol of our culture); on the back of an overcoat, an image of a woman being dragged into a paddy wagon by OMON agents (riot police); on a summer frock, a drawing of a “witch” tied to the stake, on fire.

The theme of the sacrifice of women puts the viewer in mind of Pussy Riot, who have elicited people’s bloodthirsty fantasies and calls for the most horrendously cruel forms of punishment (pussyriotlist.com). The exhibit also contains headgear made to resemble a balaclava helmet. Not explicit, but ambivalent, a kind of hint.

Gender violence is one of the recurring themes of the tragic parade of clothes. It seems to be no accident that Gluklya’s exhibit at the Venice Biennial opened around the same time as Alketa Xhafa-Mripa’s installation at the stadium in Prishtina, Kosovo (http://www.wonderzine.com/wonderzine/life/news/214075-thinking-of-you; Xhafa-Mripa, born in Kosovo, lives in Great Britain): there, a few thousand dresses and skirts, hung up on white ropes, testify to the sexual violence that occurred on a mass scale during the armed conflict in Kosovo of 1998–1999.

Dress Code

In Ludmila Ulitskaya’s novel The Funeral Party, Robins formerly Rabinovich, the far-sighted owner of a funeral home, “had difficulty in determining the client’s property status” at a funeral attended not only by Jews but also by blacks, American Indians, rich Anglo-Saxons and “numerous Russians,” comprising both “respectable citizens” and “out-and-out scoundrels.” Can social status be determined by protest clothing? Here, too, were various sorts of people: office clerks in waistcoats, hippie-punk-goths, sophisticated women and Poor Lizas, ballerinas and Lovelaces. Their clothing—the body of their souls—is torn and in danger. They, too, are the targets of Gluklya’s reproach: “Are all of us really like this torn old rag?”

LE CHOC DE L’ACTUALITÉ À LA BIENNALE DE VENISE

A l’Arsenal, c’est l’artiste russe Gluklya qui dénonce le durcissement du régime de Moscou, à travers ses “Vêtements pour manifestations contre de fausses élections de Vladimir Poutine”.

Perchés sur des madriers en bois, ces drôles de pièces de tissu portent des messages en russe: “un voleur doit être assis en prison”, “je veux que la Russie devienne le plus beau pays du monde” ou seulement “va-t-en”.

Venice Biennale articles

http://mirror522.graniru.info/blogs/free/entries/242508.html

http://metropolism.com/reviews/homo-faber/

https://artattackapp.wordpress.com/2015/05/20/artattack-venice-biennale-2015-arsenale/

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/news/155541/

http://www.24heures.ch/culture/Le-choc-de-l-actualite-a-la-Biennale-de-Venise/story/15034018

http://www.artspace.com/magazine/news_events/okwui-enwezor-venice-2015

Burning the Dress of alienation 2015

REVIEW: INTELLIGENT, IMAGINATIVE WORK FROM AUSSIES AT 56TH VENICE BIENNALE

In the best of all possible worlds one would hope to find works of art that are both visually engaging and layered with meaning. Of 136 artists or groups of artists featured in the International exhibitions, very few made me pause. One of them was Russia’s Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya Gluklya, who contributed a suite of clothes and placards for an anti-Putin demonstration, with many surreal, startling touches. Considering the treatment dished out to the band, Pussy Riot, Gluklya’s work was as politically edgy as anything in the show, but also witty and inventive.

All the World’s Futures

It fills us with pride to say that Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition All the World’s Futures, currently at the Venice Biennale and displaying the work of Gluklya, is appreciated as being “frighteningly necessary.”

Artspace writes the following: In this show, Enwezor has tapped an impressive number of artists who ignore the market enough to speak truth to power—sometimes to the extent that it’s not obvious that what they’re doing is art. Their ethos may be best summarized by the Russian artist known as Gluklya, who co-wrote a 2002 manifesto declaring that “The place of the artist is by the side of the weak.” Her work, featured in the show, has been characterized by an exploration of the nature of public and private space in Putin’s Russia.

GLUKLYA / Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya, Clothes for the demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin, 2011-2015, textile, hand writing, wood, Courtesy AKINCI Amsterdam, sponsored by V-A-C Foundation, Moscow.

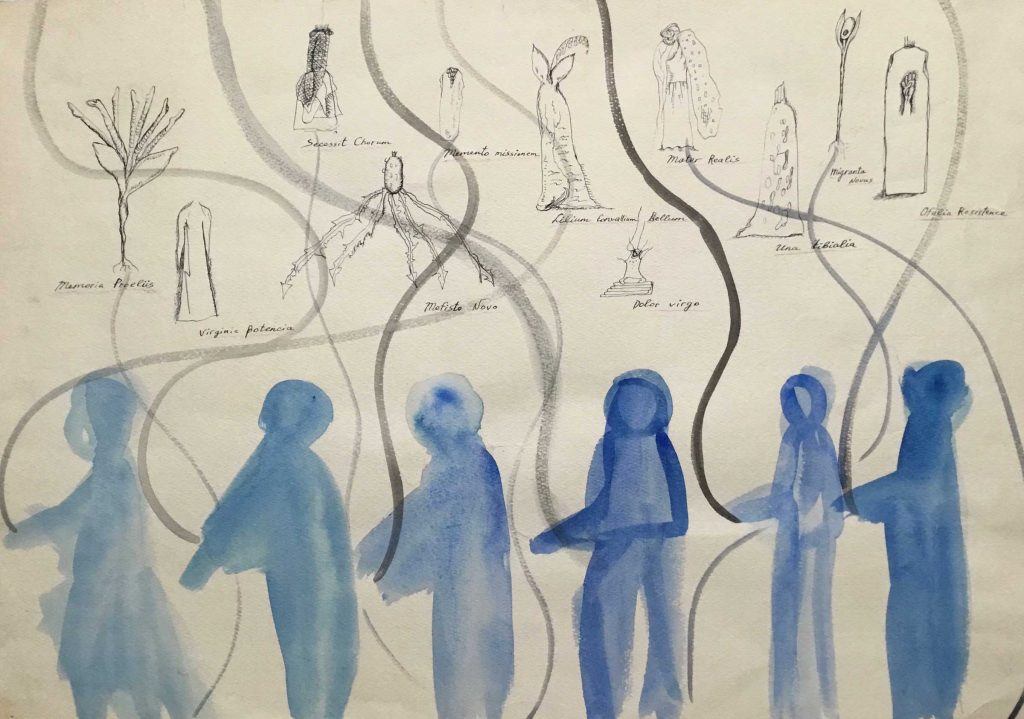

Garden of Vigilant Clothes

Interview with Anna Battista, 2015

56th Venice Biennale, 19 May, 2015

Garments as Private Narration, Garments as Public Political Banners: Gluklya’s Clothes for the Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin

Clothes transform, describe and define us, revealing what we are and often sending out messages to the people surrounding us. But, if garments are a form of non-verbal communication, they can be used to silently tell the story of our lives, they help us explaining how we may feel on a day to day basis, and they could even be employed as political statements or banners to protest and make our voices heard. At least that’s what artist Natalya Pershina-Yakimanskaya – better known as Gluklya – suggests us. Born in Leningrad and dividing her time between Saint Petersburg and Amsterdam, Gluklya has developed quite a few projects moving from clothes and garments. Together with Olga Egorova (Tsaplya) she be-came a co-founder in 1995 of artist collective The Factory of Found Clothes (FFC; in 2012 Gluklya took over the leadership of the group, while becoming also an active member of the Chto Delat?—meaning “What is to be done?”—platform). The collective was mainly set to tackle, through installations, performances, videos and social re-search, modern issues such as the dichotomy between the private and the public sphere or the position of marginal and liminal groups of people in our society.

In Gluklya’s practice clothes transform therefore into tools, elements that link and connect art and everyday life. In her latest installation currently on display at Venice’s Arsenale during the 56th International Art Exhibition, the artist questions visitors about the legitimacy of Putin’s election. Derived from the FFC’s ongoing performance ‘Utopian Clothes Shop’ (2004-), “Clothes for the demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin” (2011-2015) consists in a series of garments hung on wooden posts, like banners. Each garment is different from the other: there are white tutu-like tulle dresses and heavy coats in military green; partially burnt garments with slogans such as ‘Stop Slavery!’ and pieces decorated with prints or embroidered motifs; a dress with a large red rose appliqued around the chest area tragically evokes blood, while black cones of fabric conceptually erupt from one simple white dress and a random valenki boot provides a temporary and surreal head for one of these silent protesting banners.

Though different one from the next, all the vestments have the same purpose: they challenge the legitimacy of Vladimir Putin’s re-election to president. In this way the garments cross the private and personal sphere, changing aim and objective, turning into public and political weapons, assuming new values and meanings, and becoming even more ominous when considering the recent reports by monitor organizations and Western diplomats, claiming that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is slowly continuing—even though Moscow says it’s sticking to a ceasefire agreement—and may lead to a summer offensive. “The place of the artist is on the side of the weak”, states the FFC manifesto that also considers the artist as “a friend” and “accomplice”. Gluklya’s new installation does exactly that, positioning the artist next to ordinary people and prompting them to stop being afraid and make their voices heard.

Your installation inside the Arsenale—entitled “Clothes for the demonstration against the false election of Vladimir Putin”—challenges the legitimacy of Putin’s re-election. In your opinion, how difficult it is for an artist -and in particular a woman artist and feminist -to be heard in Russia at the moment without incurring in problems such as censorship or repression?

Gluklya: I actually do not think there is much risk because people in power are not interested too much in art. Yet I do think that con-temporary art must have this risk-taking component in its concept. One of the pieces features a slogan by poet and literary theorist Pavel Arseniev, the representative voice of progressive forces, stating “Represent us? You can’t even imagine us!”

How many garments are there in your installation and what do they symbolize – fears, hopes or change?

Gluklya: The installation is part of the concept of Utopian realism, an idea I have been developing for the last 12 years. There are 43garments in this work and they symbolize the courage and internal beauty of oppressed people who decide to resist injustice. Fears, hope and change are also tackled. Through this work I also want to show people’s aggressiveness—and in particular the aggressiveness of victims—and anger, their bitterness and grief. People may be passive and patient for many years, but, eventually, a time will come when they rise and they rise with an axe. My work is about the aspect of “becoming human” and rising again after too many years spent sleeping and about the euphoria generated by being together. You could argue that the protest dramatically failed as people went again to sleep, that’s why there are some black pieces on the ground in the installation, to call to mind a graveyard, a cemetery. Yet the objects express also my tenderness and love to the people who found dignity and protested.

Did you take inspiration for the garments from any particular Russian artist such as Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova for what regards the shapes, colors and themes?

Gluklya: I do not actually call them “garments” as I conceive them as “speaking clothes”. I love Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova of course, but I did not take inspiration from them. The inspiration comes from the Russian avant-garde in general and that unique historical moment when art and politics were united together.

In your installation you use clothes almost as banners. Your coats, dresses or shirts include indeed slogans, pictures, or cones of fabric that protrude from them. Do you feel that at the moment in Russia it is important first to be seen in order to be heard?

Gluklya: If I were a a singer or a speaker, I would say that to be heard is the most important thing. But as a visual artist I think this is the most organic way to express my ideas.

Did you ever think about working with a Russian fashion designer and maybe develop a collection of clothes that may provide people with garments charged with political meanings?

Gluklya: That would be great, but I wouldn’t do it with a Russian designer or any other fashion designers, maybe I would do it with a clever producer. It would be great to know somebody in the UK for example who may be interested.

In this year’s Biennale quite a few artists responded to Okwui Enwezor’s brief ‘All the World’s Futures’ with works focusing on themes such as politics, immigration and social issues. In which ways can art be turned into a powerful weapon for the most disenfranchised people in the world in a context such as the Venice Biennale where there are many wealthy visitors, collectors and gallerists?

Gluklya: That is actually a sophisticated question for a PhD dissertation, a book or a film. I think you have to try your best to be honest with yourself and other people and doing good art which can move somebody and force them to think also in other directions, and ponder more about the world’s situation rather than just about finding a strategy to raise your own personal capital. Actually, at the beginning of my involvement in this year’s Biennale when it wasn’t clear yet what I was going to show, I proposed to let in for free all those people bringing with them some clothes that had a story. This idea came from my long-term project entitled the Museum of the Utopian Clothes.

Will you be taking part in any other events/exhibitions in the next few months?

Gluklya: My video ‘Wings of Migrants’ (which Okwui also wants to show at the Biennale) and other works were on display until last week at the Barbara Gross Gallery in Munich, as part of the event ‘Female Views on Russia’ that also features Anna Jermolaewa and Taisiya Krugovykh. I’m also working on the installation dedicated to Joseph Brodsky at the Achmatova Garden in Saint Petersburg and on a social opera with the TOK curatorial team about the struggle of local people against gentrification and other infringed human rights. I’m currently thinking of working with special fire resistant textiles, a discovery I made while I focused on the installation for the Biennale. I do also hope that I will find the necessary funds to make a new theatre performance—’Debates on Division N. 2’ (the first ‘Debates’ took place at Manifesta this year)—in Tbilisi, Georgia. Clothes for Demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin 2011-2015 Installation overview ‘All the World’s Futures,’ 56th Venice Biennale, 2015