In the best of all possible worlds one would hope to find works of art that are both visually engaging and layered with meaning. Of 136 artists or groups of artists featured in the International exhibitions, very few made me pause. One of them was Russia’s Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya Gluklya, who contributed a suite of clothes and placards for an anti-Putin demonstration, with many surreal, startling touches. Considering the treatment dished out to the band, Pussy Riot, Gluklya’s work was as politically edgy as anything in the show, but also witty and inventive.

Interview with Anna Battista, 2015

56th Venice Biennale, 19 May, 2015

Garments as Private Narration, Garments as Public Political Banners: Gluklya’s Clothes for the Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin

Clothes transform, describe and define us, revealing what we are and often sending out messages to the people surrounding us. But, if garments are a form of non-verbal communication, they can be used to silently tell the story of our lives, they help us explaining how we may feel on a day to day basis, and they could even be employed as political statements or banners to protest and make our voices heard. At least that’s what artist Natalya Pershina-Yakimanskaya – better known as Gluklya – suggests us. Born in Leningrad and dividing her time between Saint Petersburg and Amsterdam, Gluklya has developed quite a few projects moving from clothes and garments. Together with Olga Egorova (Tsaplya) she be-came a co-founder in 1995 of artist collective The Factory of Found Clothes (FFC; in 2012 Gluklya took over the leadership of the group, while becoming also an active member of the Chto Delat?—meaning “What is to be done?”—platform). The collective was mainly set to tackle, through installations, performances, videos and social re-search, modern issues such as the dichotomy between the private and the public sphere or the position of marginal and liminal groups of people in our society.

In Gluklya’s practice clothes transform therefore into tools, elements that link and connect art and everyday life. In her latest installation currently on display at Venice’s Arsenale during the 56th International Art Exhibition, the artist questions visitors about the legitimacy of Putin’s election. Derived from the FFC’s ongoing performance ‘Utopian Clothes Shop’ (2004-), “Clothes for the demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin” (2011-2015) consists in a series of garments hung on wooden posts, like banners. Each garment is different from the other: there are white tutu-like tulle dresses and heavy coats in military green; partially burnt garments with slogans such as ‘Stop Slavery!’ and pieces decorated with prints or embroidered motifs; a dress with a large red rose appliqued around the chest area tragically evokes blood, while black cones of fabric conceptually erupt from one simple white dress and a random valenki boot provides a temporary and surreal head for one of these silent protesting banners.

Though different one from the next, all the vestments have the same purpose: they challenge the legitimacy of Vladimir Putin’s re-election to president. In this way the garments cross the private and personal sphere, changing aim and objective, turning into public and political weapons, assuming new values and meanings, and becoming even more ominous when considering the recent reports by monitor organizations and Western diplomats, claiming that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is slowly continuing—even though Moscow says it’s sticking to a ceasefire agreement—and may lead to a summer offensive. “The place of the artist is on the side of the weak”, states the FFC manifesto that also considers the artist as “a friend” and “accomplice”. Gluklya’s new installation does exactly that, positioning the artist next to ordinary people and prompting them to stop being afraid and make their voices heard.

Your installation inside the Arsenale—entitled “Clothes for the demonstration against the false election of Vladimir Putin”—challenges the legitimacy of Putin’s re-election. In your opinion, how difficult it is for an artist -and in particular a woman artist and feminist -to be heard in Russia at the moment without incurring in problems such as censorship or repression?

Gluklya: I actually do not think there is much risk because people in power are not interested too much in art. Yet I do think that con-temporary art must have this risk-taking component in its concept. One of the pieces features a slogan by poet and literary theorist Pavel Arseniev, the representative voice of progressive forces, stating “Represent us? You can’t even imagine us!”

How many garments are there in your installation and what do they symbolize – fears, hopes or change?

Gluklya: The installation is part of the concept of Utopian realism, an idea I have been developing for the last 12 years. There are 43garments in this work and they symbolize the courage and internal beauty of oppressed people who decide to resist injustice. Fears, hope and change are also tackled. Through this work I also want to show people’s aggressiveness—and in particular the aggressiveness of victims—and anger, their bitterness and grief. People may be passive and patient for many years, but, eventually, a time will come when they rise and they rise with an axe. My work is about the aspect of “becoming human” and rising again after too many years spent sleeping and about the euphoria generated by being together. You could argue that the protest dramatically failed as people went again to sleep, that’s why there are some black pieces on the ground in the installation, to call to mind a graveyard, a cemetery. Yet the objects express also my tenderness and love to the people who found dignity and protested.

Did you take inspiration for the garments from any particular Russian artist such as Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova for what regards the shapes, colors and themes?

Gluklya: I do not actually call them “garments” as I conceive them as “speaking clothes”. I love Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova of course, but I did not take inspiration from them. The inspiration comes from the Russian avant-garde in general and that unique historical moment when art and politics were united together.

In your installation you use clothes almost as banners. Your coats, dresses or shirts include indeed slogans, pictures, or cones of fabric that protrude from them. Do you feel that at the moment in Russia it is important first to be seen in order to be heard?

Gluklya: If I were a a singer or a speaker, I would say that to be heard is the most important thing. But as a visual artist I think this is the most organic way to express my ideas.

Did you ever think about working with a Russian fashion designer and maybe develop a collection of clothes that may provide people with garments charged with political meanings?

Gluklya: That would be great, but I wouldn’t do it with a Russian designer or any other fashion designers, maybe I would do it with a clever producer. It would be great to know somebody in the UK for example who may be interested.

In this year’s Biennale quite a few artists responded to Okwui Enwezor’s brief ‘All the World’s Futures’ with works focusing on themes such as politics, immigration and social issues. In which ways can art be turned into a powerful weapon for the most disenfranchised people in the world in a context such as the Venice Biennale where there are many wealthy visitors, collectors and gallerists?

Gluklya: That is actually a sophisticated question for a PhD dissertation, a book or a film. I think you have to try your best to be honest with yourself and other people and doing good art which can move somebody and force them to think also in other directions, and ponder more about the world’s situation rather than just about finding a strategy to raise your own personal capital. Actually, at the beginning of my involvement in this year’s Biennale when it wasn’t clear yet what I was going to show, I proposed to let in for free all those people bringing with them some clothes that had a story. This idea came from my long-term project entitled the Museum of the Utopian Clothes.

Will you be taking part in any other events/exhibitions in the next few months?

Gluklya: My video ‘Wings of Migrants’ (which Okwui also wants to show at the Biennale) and other works were on display until last week at the Barbara Gross Gallery in Munich, as part of the event ‘Female Views on Russia’ that also features Anna Jermolaewa and Taisiya Krugovykh. I’m also working on the installation dedicated to Joseph Brodsky at the Achmatova Garden in Saint Petersburg and on a social opera with the TOK curatorial team about the struggle of local people against gentrification and other infringed human rights. I’m currently thinking of working with special fire resistant textiles, a discovery I made while I focused on the installation for the Biennale. I do also hope that I will find the necessary funds to make a new theatre performance—’Debates on Division N. 2’ (the first ‘Debates’ took place at Manifesta this year)—in Tbilisi, Georgia. Clothes for Demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin 2011-2015 Installation overview ‘All the World’s Futures,’ 56th Venice Biennale, 2015

Installations Utopian Unions

Installation ММОМА/Moscow/2013

Wings of Migrants. A transparent reseach

Wings of Migrants

| September 8 – October 13, 2012 Opening September 8, 5 – 7 pm |

|

| Gluklya – Wings of Migrants | |

|

|

| Gluklya, ‘Wings of Migrants’, 2012, still from video | |

| AKINCI proudly announces the first exhibition of Factory of Found Clothes (FFC) presented by the Russian artist Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya) with the project ‘Wings of Migrants’.

This project by Gluklya is presented at AKINCI as a ‘transparent research’ and focuses on migrants who come to Russia from the former Soviet Union. Migrants are often used as unskilled and low-paid workers, as a rule displaced to the periphery of society. This closure is determined by the deprived and often illegal status of migrants, as well as by the culture and language differences. The film ‘Wings of Migrants’ which forms part of the show, is a collective collaboration with the “No dance company” in St-Petersburg. It started from the idea to create a long term project: ‘Theatre for migrants’. There is a historical link to the ‘Proletkult theatre’ (1920) of Ezenshtain and Tretyakov, who went to the GAZ factory (Gazovii Zavod) to play theatre. The idea of FFC was to create an encounter with dancers and migrant workers in order to invite them to become part of an utopian situation where they all can exist together in an equal position. The film was realized in one of the oldest factories in St-Petersburg. The film ‘Wings of Migrants’ was supported by the Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies, UvA and co-produced with Dr. Olga Sezneva. Financial support also came from Hugh Scott (Adventures of seeing), free lance curator from the UK and Leyla Akinci, Amsterdam. Special thanks go to the great artist and feminist, Susan Morlan from the UK, as well as all who participated in the research : No Dance Company, Olga Denisova, Andrei Yakimov from Memorial, Aya Yakimova, Urii Shtopakov , Tsaplya Egorova, Angelika Artuh, and others. On September 27th at 7 pm AKINCI will host a round table discussion focusing on issues connected to the use of aesthetics in exploring and intervening in socio-political realities with: Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), artist, founding member of FFC and member of Chto Delat? Olga Sezneva, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Co-director of IMES, UvA Gluklya (Natalia Pershina Yakimanskaya) works within two collectives (since 1995 she collaborates with Olga Eorova (Tsaplya) in ‘The Factory of Found Clothes’ and since 2003 Gluklya is part of the artist group ‘Chto delat?’) as well as doing her own research, combining performance, environmental works, situationist actions, video, and direct contact. Glukly’s work has been exhibited in Russia and abroad, including the MUMOK, Vienna (2012). the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden Baden (2011), Shedhalle, Zurich (2011), SMART Project Space, Amsterdam (2011), Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid (2011), Kunsthalle, Vienna (2011), ICA, London (2010), Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (2011 & 2009), Thessaloniki Biennale (2009), Museum of Contemporary Art, Kalmar (2008), Botkyrka Konsthall,Stokholm (2007), National Center for Contemporary Art, Moscow (2006), National contemporary art museum Oslo (2005) |

|

| AKINCI • LIJNBAANSGRACHT 317 • NL–1017 WZ AMSTERDAM • T +31(0)20 638 04 80 • INFO@AKINCI.NL • WWW.AKINCI.NL |

Wings of Migrants in Amsterdam – Preparing

Installation Amsterdam, Pensioner’s Resist

SHELTERS FOR MIGRANTS

“Fragility and Power” Installation in ICA /Chto Delat Project

THE GREATEST IDIOT OF NEW ZEALAND

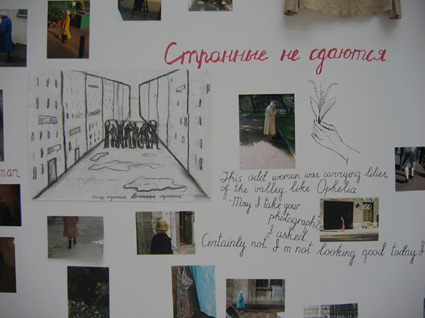

Strange People Never Surender, 2005

1th Prague Bienniale – curator Aleksandra Arhipova, Moscow

The Strange Never Give Up

Installation, 2005

The installation consists of a) a table with photographs of the “Strange”. Notes and commentaries, written by hand, b) a clothes-hanger with clothes of a special design, projected to reflect the inner world of the “Strange”. Strolling around Narvskaya Zastava, you can find them everywhere. They are everpresent, coursing through the world’s capillaries like blood cells. Usually, the beauty of the “Strange” goes unnoticed, even if there are far more of them than people who live on the borderline, who have nothing left in common with society at large, such as the homeless, lying around on the asphalt, the “Full-Blues”*, who are hardly strange at all; instead, they provoke feelings of horror, pinching sorrow, pity, or anger. The “Strange”, however, provoke a feelings of surprise and exaltation, maybe because these people continue to exist, despite the inescapable poverty of their fate. Just look at how they dress! Their clothing is armored plating, designed to defend us from the heaviness of reality! There can be little doubt that the life of the Strange is reflected in their costumes. I swear: these people are far freer than the “Full-Blues” or that the “Well-Dressed”. The slight madness of the Strange eloquently tells us that they live in their own world; often, they march forward at a determined pace, busily carrying their burden in an elegant plastic bag…